Before we begin

The practice of praying both sides—for yourself and for others—will stretch your prayer and your imagination, inviting you to consider how God may be calling you to widen your circles of concern and compassion.

Over the years as I have grown in my own practice of praying both sides, I found how this imaginative, expansive approach is intimately connected to our images of God. As we learn to pray for others and ourselves in new ways, we begin to understand God in new ways, too. So part of learning to pray both sides is not only expanding your prayer list, but exploring a rich variety of images for God from Scripture.

Each Sunday in Lent I’ll share the pairing of two opposite titles, features, or attributes of God that reveal more of the mystery held within such tensions. For example, God is called both Father and Son in the Gospels. How does our prayer shift depending on whom we picture when we pray? In the Book of Isaiah, the prophet describes God as a fierce warrior and a laboring mother. How do these two seemingly contradictory images of God invite us to consider different aspects of the divine mystery?

In these “mini-chapters” for each week of Lent, I’ll offer you:

two Scripture passages with different images of God

an essay exploring “both sides” of God

a breath prayer as a simple way to meditate on this mystery

examples of ways to pray both sides with these images of God

an invitation to offer your own petitions so we can keep praying together

A note to free subscribers: I promise not to clutter your inboxes with extra emails. But today I wanted to give you a taste of these reflections, in case you want to decide you’d like to read more. You can join us to receive them with a paid membership of only $5/month for Lent.

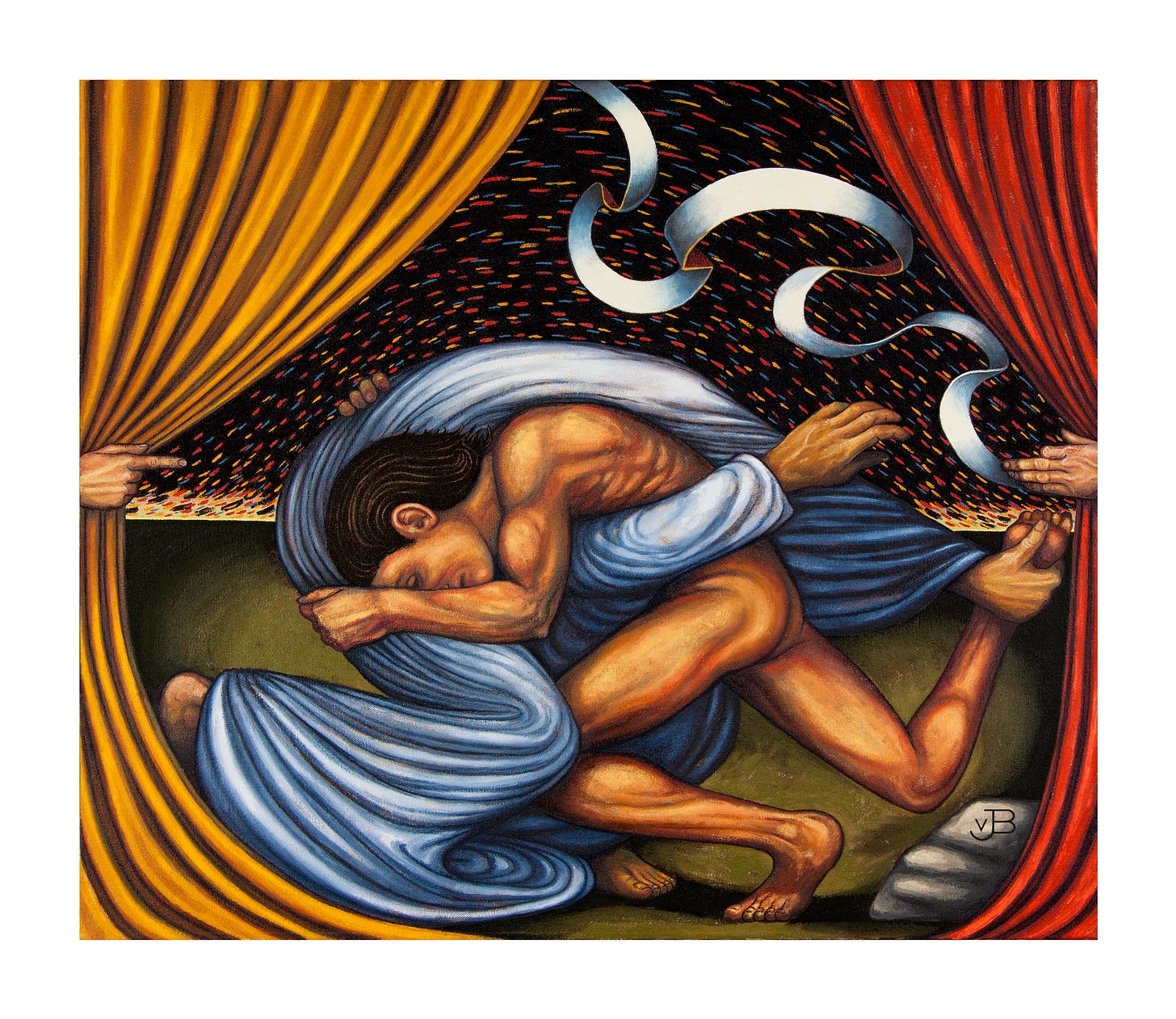

God is both wrestler and consoler

Jacob was left alone; and a man wrestled with him until daybreak. When the man saw that he did not prevail against Jacob, he struck him on the hip socket; and Jacob’s hip was put out of joint as he wrestled with him. Then he said, ‘Let me go, for the day is breaking.’ But Jacob said, ‘I will not let you go, unless you bless me.’ So he said to him, ‘What is your name?’ And he said, ‘Jacob.’ Then the man said, ‘You shall no longer be called Jacob, but Israel, for you have striven with God and with humans, and have prevailed.’ Then Jacob asked him, ‘Please tell me your name.’ But he said, ‘Why is it that you ask my name?’ And there he blessed him. So Jacob called the place Peniel, saying, ‘For I have seen God face to face, and yet my life is preserved.’

(Gen 32:24-30)

Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Father of mercies and the God of all consolation, who consoles us in all our affliction, so that we may be able to console those who are in any affliction with the consolation with which we ourselves are consoled by God.

(2 Cor 1:3-4)

To wrestle is to fight. To console is to comfort. The dictionary tells us they are antonyms, impossible to reconcile. But Lent is a time for both: wrestling with God and finding consolation. How can the source of strife be the same as the salve?

Here are two stories that meet in the middle.

//

After my daughters died, my sister came to stay. We wedged an air mattress into my office, and she slept there for many nights. I cannot remember how long; eight years have sifted dust over memory. But I know it was Lent, I know my heart and body were broken, and I know she was there.

As I burrowed upstairs in bed in grief, recovering from a c-section with no babies to hold, she wrestled with my boys. Every morning, bright or gloomy, all three of them raced downstairs and shoved open the office door, diving onto the air mattress, jumping and whooping like hyenas. In footie pajamas and sleep-tousled hair, they wrestled with her at dawn. She knew they needed to fight out their grief, even through play, even beyond words.

We still laugh about that, she and I. The children have grown now; the grief has, too. But we remember the wrestling.

//

People ask me all the time now: How are the kids?

I stare at them for a split second, wondering what words to speak. How do you think the kids are? Would you expect them to be fine after their mother was struck with cancer? Should they bounce back like rubber and forget anything ever happened, now that the deadly disease is supposedly stricken from my body? Have they forgotten months and months of our home life unraveling, every rhythm undone, every routine disrupted, their mother sick upstairs, their father trying to do everything for two?

Good, I say. Because no one wants to hear the truth.